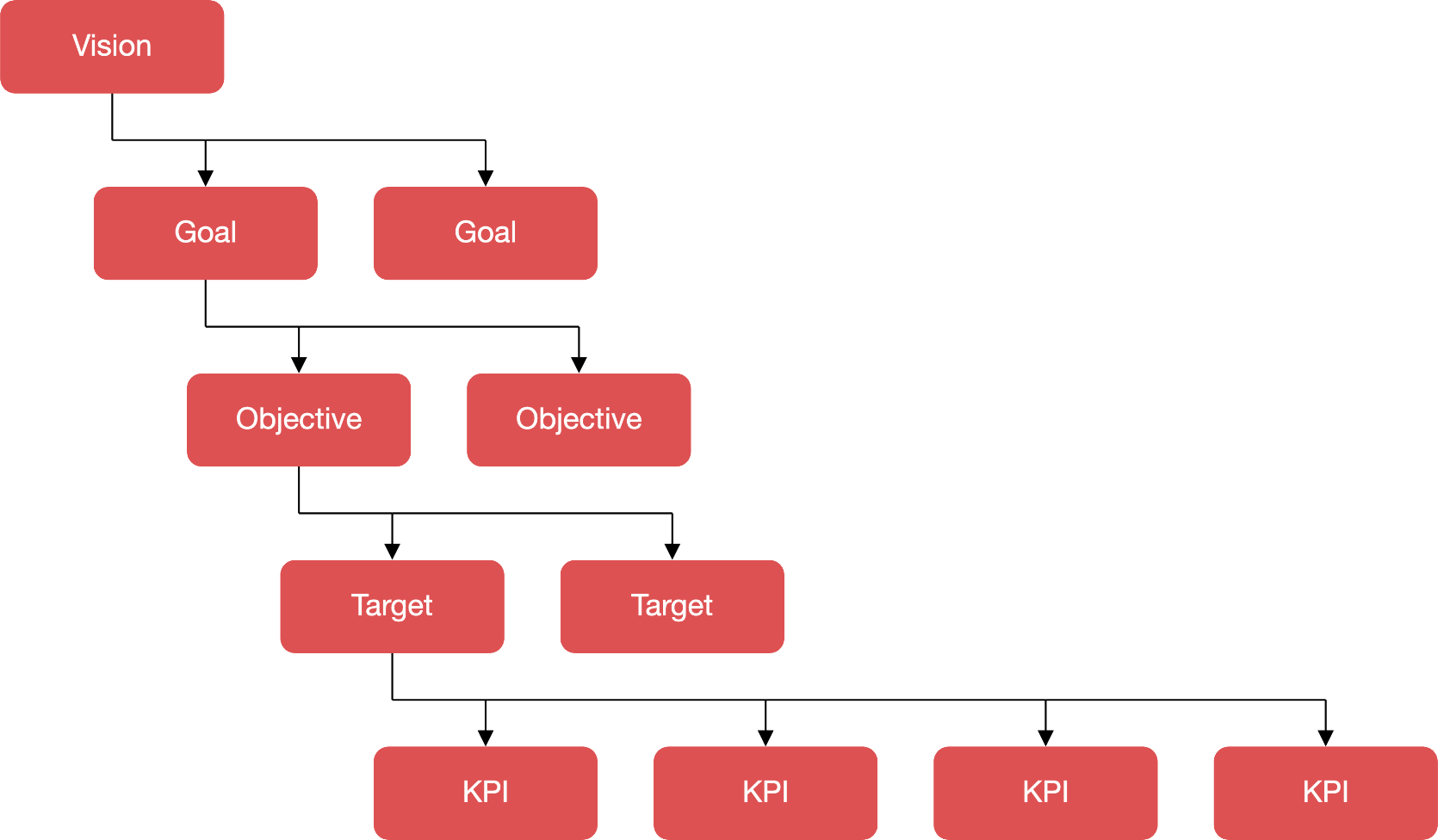

Once a set of goals and objectives has been established in accordance with the agreed vision, it will be important to set targets and indicators (KPIs).Setting sustainability targets is fundamental when developing a sustainable freight transport strategy. Targets help define, in specific and measurable terms, the desired outcomes of the strategy. They should be incorporated into a vision statement to contribute to a "SMART" objective. As shown below, a vision or a vision statement can have multiple goals and each goal can have many objectives. At the same time, each objective can be linked to multiple targets and each target could be linked to various KPIs. Developing targets and indicators needs to be undertaken concurrently with the formulation of objectives. Where targets and indicators are developed in isolation from the objectives, there is a risk that the indicators start to drive rather than support the decision-making process.

Translating vision into goals, objectives, targets and key performance indicators

Benefits of setting sustainability targets include:

- Establishing clear goals for various stakeholders and purposes (e.g. public authorities/organisations, projects, investments, etc.).

- Motivating people working in the freight transport sector by clarifying their expected performance and how they can measure progress (or lack thereof).

- Providing a benchmark against which improvements can be measured.

- Demonstrating commitment to the sustainable freight transport agenda.

- Generating potential marketing benefits.

Targets help to set up a clear course of action and guide future direction. By providing relevant benchmarks, targets provide a measure of how successful the strategy may have been and determine required adjustment to improve performance and results. As freight transport is a multi-faceted area of activity, targets should be clear and there should be no ambiguity about the objective that is being prioritized. This ensures that stakeholders understand how the different objectives are being balanced. This in turn, can help secure stakeholders’ buy-in and support.

Relevant examples relating to Visions and Targets, including as applied in the freight transport sector are featured in the tables below.

Examples of sustainability targets and visions

| Name | Market | Vision | Goals/Objectives/Targets | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | To drive efficient and sustainable freight logistics that balance the needs of a growing Australian community and economy with the quality of life aspirations of the Australian people. | To improve the efficiency of freight movements across infrastructure networks, to minimise externalities associated with such freight movements and to influence policy making of relevance to freight. | Qualitative target

Applies across the freight transport sector (all modes). | |

| California Sustainable Freight Action Plan | State | Utilise a partnership of federal, State, regional, local, community, and industry stakeholders to move freight in California on a modern, safe, integrated, and resilient system that continues to support California’s economy, jobs, and healthy, liveable communities. Transporting freight reliably and efficiently by zero-emission equipment everywhere feasible, and near-zero emission equipment powered by clean, low-carbon renewable fuels everywhere else. |

| Quantitative target.

Applies across the freight transport sector (all modes).

Social aspects not prioritised. |

| DHL | Shipper, supply chain manager, carrier, retailer, wholesaler, freight transport/logistics service provider | To be The Logistics Company for the World. | Reduce the greenhouse gas emissions for every letter, every parcel, every ton of freight and every square meter of warehouse space by 30% by the year 2020. | Quantitative target.

Applies across the transport service provider logistics sector.

Only environmental aspects prioritised. |

| The Stockholm Freight Plan 2014–2017 | City | An initiative for safe, clean and efficient freight deliveries The Stockholm Freight Plan 2014–2017 is part of the City’s commitment to a world-class Stockholm. The vision presents three coherent themes for the city’s development, as well as a number of essential characteristics that show what it will be like to live in, work in and visit Stockholm in the year 2030. | Four goals for 2014-2017 period: The city aims to

| Qualitative target.

Applies across the freight transport sector (all modes). |

| EU Transport White Paper | Regional | Growing Transport and supporting mobility while reaching the 60% emission reduction target | Achieve essentially CO2-free city logistics in major urban centers by 2030, Low-carbon sustainable fuels in aviation to reach 40% by 2050; also by 2050 reduce EU CO2 emissions from maritime bunker fuels by 40%, 30% of road freight over 300 km should shift to other modes such as rail or waterborne transport by 2030, and more than 50% by 2050, facilitated by efficient and green freight corridors, a fully functional and EU-wide multimodal TEN-T ‘core network’ by 2030, with a high quality and capacity network by 2050 and a corresponding set of information services, by 2050, move close to zero fatalities in road transport, full application of “user pays” and “polluter pays” principles. | Quantitative target.

Applies across the freight transport sector (all modes). |

| A.P. Møller - Mærsk A/S | Transport, logistics and energy provider | We aspire to unlock growth – for society and Maersk. We will achieve this through the core strengths of our businesses and by being a responsible business partner. |

[Selection] | Quantitative targets Social aspects also included |

Examples of relevant freight transport sector targets

| Stakeholder | Targets relevant to the freight transport sector | Target type | Sustainability dimensions | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic | Environmental | Social | |||

| EU Transport White Paper | Achieve essentially CO2-free city logistics in major urban centers by 2030, Low-carbon sustainable fuels in aviation to reach 40% by 2050; also by 2050 reduce EU CO2 emissions from maritime bunker fuels by 40%, 30% of road freight over 300 km should shift to other modes such as rail or waterborne transport by 2030, and more than 50% by 2050 | Absolute target considering mode share, fuel type and emissions |

|

|

|

| Bangladesh | Freight mode share target of 20% for inland waterways and 10% for railways for 2009–2014 | Absolute target in modeshare |

|

|

|

| IATA | An average improvement in fuel efficiency of 1.5% per year from 2009 to 2020, A cap on net aviation CO2 emissions from 2020 (carbon-neutral growth), A reduction in net aviation CO2 emissions of 50% by 2050, relative to 2005 levels | Absolute and intensity targets combined |

|

|

|

| Fujitsu Group | To reduce CO2 emissions in domestic distribution by 11% compared to FY 2008 by the end of FY 2012. | Absolute target in reducing emissions |

|

|

|

| Komatsu | To cut CO2 emissions from transportation of products and parts to 66kt per cargo weight (basic unit) in FY 2022. 43% or more reduction in CO2 emissions (as compared to 2010 levels) as the goal for FY 2022. 50% reduction in CO2 emissions as the goal for 2030 and becoming carbon neutral by 2050 | Absolute target and intensity target considering emissions per cargo weight combined |

|

|

|

| SDGs | By 2020, halve the number of global deaths and injuries from road traffic accidents. By 2030, substantially reduce the number of deaths and illnesses from hazardous chemicals and air, water, and soil pollution and contamination. By 2030, improve water quality by reducing pollution, eliminating dumping and minimising the release of hazardous chemicals and materials, halving the proportion of untreated wastewater, and increasing recycling and safe reuse by x% globally. Double the global rate of improvement in energy efficiency by 2030. Increase substantially the share of renewable energy in the global energy mix by 2030. Increase significantly the exports of developing countries, in particular with a view to doubling the LDC share of global exports by 2020. | Absolute and intensity targets combined | |||

Note: Fully considered; Partially considered; Not considered

When selecting targets, it is important to bear in mind the difference between the top-down and the bottom-up approaches.

Top-down vs bottom-up targets

Top-down freight transport targets are usually set based on a given ambition without any scientific quantification and justification. In most cases, they are not based on a detailed analysis of the mitigation potential. Instead, they are often aligned with targets quoted by competitors, trade bodies and/or government agencies. These targets often do not consider operational, technological, and financial constraints and do not take into account cross-functional variations in the potential for externalities abatement and its cost–effectiveness.

In contrast, bottom-up targets or activity-based targets take into account operational, technological, financial, and cost-effectiveness considerations. They are generally based on bottom-up quantifications that clarify the mitigation potential of relevant policies and measures.

Absolute vs intensity targets

Absolute targets reduce the total amount of externalities or impacts regardless of changes in the level of activity. Countries or private sector companies may fear that the pursuit of an absolute reduction target will constrain the growth of their economy and business activities, and potentially carry a financial penalty. In this context, sustainability targets in the freight transport sector could often be intensity-related. Sustainability parameters are expressed in relative terms and are linked with an appropriate normalizer (e.g. emissions per ton-kilometre, emissions per vehicle-kilometre or freight fatalities per freight vehicle-kilometre). Targets can also be developed based on a tier approach where differentiation is made between the short and longer-term goals. Once finalized, targets ultimately set the course for future action. Table 5 features the type of targets used by some relevant stakeholders when devising and implementing their respective sustainable freight transport strategies.

These targets are monitored using KPIs, which are inherently linked to the objectives and goals. KPIs are indicators used to assess whether stakeholders are on target as they work towards achieving the vision’s goals and objectives. Indicators may need to be refined over time and improved to better reflect stakeholders’ needs. For example, the policy priorities may change due to new and emerging critical challenges or there could be new developments in statistical methodologies and data availability, creating new opportunities for indicator refinement. Thus, some level of flexibility should be allowed when developing indicators. This aspect is elaborated further under the Monitoring and Evaluation step.

To support the selection of KPIs that address the economic, social, and environmental sustainability of freight transportation, around 200 indicators have been compiled under the UNCTAD SFT Framework. The list of KPIs compiled by UNCTAD, which can be displayed using various filters and criteria (e.g. by transport mode, scope and sustainability dimension), illustrates how different indicators can be formulated at different scales to measure different objectives (see Tool on UNCTAD SFT Key Performance Indicators). It should be noted however, that these indicators are not intended to serve as a complete or comprehensive list of KPIs in the field of sustainable freight transport.

When selecting the KPIs to be tracked, stakeholders’ involvement is necessary. Targets and KPIs must also be accepted by all the parties that are expected to take responsibility for their achievement. Consulting stakeholders, including stakeholders identified during the Diagnosis and Visioning steps, is required to generate support for the KPIs and targets and to discuss the measures that are most important. Stakeholders need to decide who should be compiling information about the relevant measures and agree on how to link these measures to the strategies developed and implemented to achieve sustainable freight transportation. Consultations could also help address potential data gaps and double counting.

Efforts should aim to improve the freight transport-related data sources, availability, granularity, reliability and quality. Improved data systems can support the development of useful indicators, which in turn, are crucial enablers of sound and informed decision-making processes. This is particularly true in many developing countries, where limited access to freight transport-related data could undermine evidence-based decision-making.